While working at Atlantic Records Recording Studios in New York City, I came to realize how the rest of the world made records. Up until then, I only knew how my Dad did it. The difference in methods made me question how Dad made all those great sounds in the garage studio and hit recordings while traveling all over the country. Dad would have a smile on his face every time the subject came up. There would always be a little of the professor in him that would come out when he explained the recording process to me. When Dad first started multi-layering instrumentals in his garage in Hollywood, he used the disc-to-disc recording technique using one cutting lathe to record and a disk player turntable to playback. To achieve the unusual guitar effects he wanted, he needed to build a second cutting lathe that gave him disc playback and record abilities at 78 rpm and half speed at 39 rpm. The second lathe enabled him to record his guitar an octave higher than normal. He quickly realized there would be many rules he needed to follow. The first rule was in what order the instruments and parts should be recorded. He found the balance would change the low frequencies after adding many parts and knew the mix balance of the bass was crucial and therefore had to be one of the last parts to be added. Also, when adding the bass part, if he noticed a note was soft in level, he would play that note louder. He never would use a limiter or compressor. Also, his guitar was low impedance, allowing him to go directly into the mixer. Dad was never a believer in using an electronic equalizer first. He would rely on the right microphone and proximity to get the sound he wanted. Using this technique, Dad taught Mary his method of close miking.

Finally, you had to have a clean chain: microphone, preamp, volume pot, recorder with no distortion, hums, or hiss. Dad would always say, "you have to know your equipment first."

The search for the New Sound led Dad to draw on his many past career experiences. His early musical influences started with his early radio DJ days in Chicago, then his Jazz Trio, and on to Fred Waring's Pennsylvanians with a complete 65-member orchestra with strings and a Glee Club. He then went on to perform with the Andrew Sisters and, after being drafted, the Armed Forces Radio Services, which brought him in everyday contact with the top talents in show business: Judy Garland, Rudy Vallee, Kate Smith, and Bing Crosby, among others, all found it's way into his New Sound.

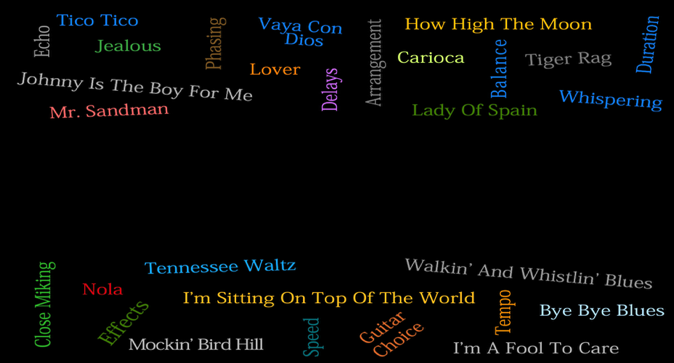

When I asked Dad to explain disc-to-disc recording, here is what he said:

"I would start by recording the first guitar part to disc #1 on cutting lathe #1, then using that disc; I would play it back on the turntable or the second cutting lathe while adding the second part using a new blank disc on cutting lathe #1. At the same time, I would balance each new part in the mix live, repeating this process, and recording as many as 30 parts for one song."

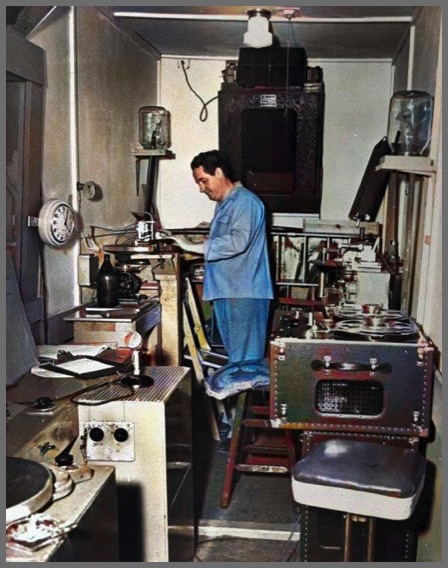

LES IN HIS HOLLYWOOD GARAGE STUDIO IN THE LATE 1940S

From Disc-To-Disc to Sound-on-Sound:

When the Ampex tape recorder came into his life through

Bing Crosby in 1949, Dad seized the moment by adding a fourth head (In Red) to make it possible to record Sound-On-Sound for the first time on tape. It also allowed him to record anywhere at any time he wanted. Sound-On-Sound is recording on tape the first part, playing it back, and adding the second part.

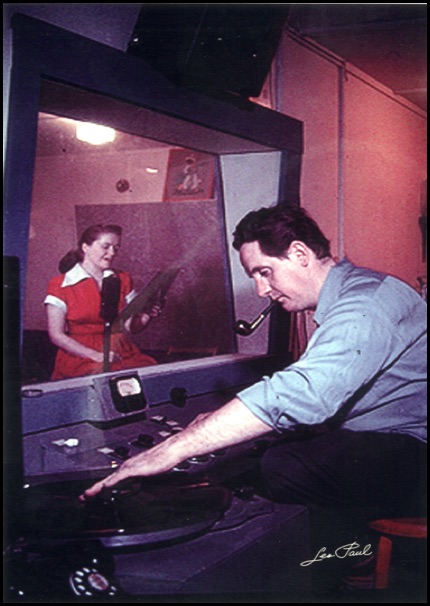

MARY RECORDING USING THE RCA 44 BX MICROPHONE.

THE SOUND ON SOUND PORTABLE EQUIPMENT

RECORDING IN THEIR BEDROOM

The next question for Dad was how he approached the recording of the arrangement:

"I had to know the arrangement in my head before I would start. I would begin with the unimportant parts first, such as slapping the guitar for the rhythm track and then continue to record the more critical tracks until finally leading up to the lead and bass parts. Like my guitar parts, Mary would record her vocals, including the many background vocal parts needed, using the same technique as me, the last part leading up to the lead vocal last, and THAT was HARD to do."

It sounds simple, but like Disc-to-Disc, recording Sound-On-Sound also came with rules. The first rule was if you made a mistake, you lost all the previous recordings and had to start over from the beginning. Unlike Disc-to-Disc, where you could always go back to the previous disc and try the new part again. Although still a crude method, the sound of the tape recorder was certainly a sonic step-up from the disc-to-disc method, but you still had to mix live and layer each part the same as the disc-to-disc method.

Dad went on to explain how he and Mary recorded "How High the Moon,"

"It took 24 generations to produce "How High the Moon." Mary and I recorded the song in our home studio in Jackson Heights, NY. We used just the Ampex 200 tape recorder, a power supply unit, a small homemade mixer, a Bell & Howell amplifier, a Lansing speaker, and a single RCA 44BX ribbon mic. We had two failed attempts to get the right results on tape."

Dad goes on to say.....

"We were located right across from a firehouse, and our first attempt was ruined when the siren went off. Then some planes came overhead on their way to La Guardia Airport and ruined the second one. At that point, Mary began crying and saying, 'I don't know if I can do it again,' and just when she decided she could, the guy who lived above us went to the bathroom. He must have weighed about 400 pounds, so we had to wait and wait while he took a leak and went to bed before we could go for it. You see, we'd record at night, and that kept the people upstairs awake. Mary would put a blanket over herself to isolate the sound, the guitar wasn't a problem since it went straight into the mixer and then earphones, but in this case, those folks complained because they could hear her singing the fourth part, which had a lot of high and strange stuff. Although the blanket over Mary's head added the necessary isolation, it left Mary's voice lacking the natural room sound. To fix that, I put a mike down the hall with a speaker at the other end, which created an echo effect I added to her voice. Adding the echo with Mary's vocal while recording worked perfectly."

"The first thing recorded was me rapping on the guitar. I turned the volume up and hit the strings, no chords, that was the rhythm, and it set the tempo. Then the second thing that went down was just chords. This went on and on and on as I built it up, part after part, take after take. The lead vocal and my lead guitar went on second to last, and the last thing that went on was the bass, played on the last string on my guitar. Everything was done on that guitar, my Epiphone custom; I never left it from the beginning to the end except to lay down under the tape machine and change motors or change capstans. It felt like I was under that machine much more than I was on top. In all, there were 12 guitar parts and 12 voices, and a total of about 24 takes before the result was sent to NBC and then on to Capitol. Everything was laid out like we were doing a stage show, and by the time Mary and I were ready to go, we pretty well knew what we were going to do; not lick for lick, not note for note, but just in terms of the sections. Within each section, we knew we could do anything we wished, four parts, eight parts, 12 parts, whatever, and while Mary was singing her part, I'd lay my part down at the same time."

How did the delay come about?

"In terms of the delay effect, I had a phonograph pickup behind the recording head on the cutting lathe. It took me about three years to figure that out. Every Friday night, this guy Lloyd and I would sit in a saloon and watch the fights on TV, and one time he asked me to explain what I was after in terms of echo. When I said like a guy shouting 'Hello' in the Alps and hearing it come back to him multiple times, he said, 'You mean, like if you put a playback head behind the recording head?' Oh my God, we were out of that saloon so fast. We left the girls there with 10 dollars to pay for the beer, we forgot all about the fights, and we were on our way home. It took us 10 minutes to get there, and we had that thing up and running in no time at all. We quickly realized that by moving the playback head forwards or backward, we could also change the delay timing, the whole neighborhood could hear 'Hello... hello... hello...'"

And how long did it take to achieve all this?

"I would say less than an hour. You see, I was so into it and so free, having played the song so much, that I would just press the button and go. And Mary was absolutely super. I'd tell her what I wanted, and that's what she'd put down. If I wanted her to sing a three-part harmony or whatever, that's the way it was done. What's more, it would take a stick of dynamite to change her, because once she'd got it, that was it, and she didn't have to rehearse or anything. It was the same with me. I knew what I was doing, and so as fast as I could rewind that tape, we were ready to lay the next parts down."

I asked Dad how he ever thought of approaching making a record this way.

"First, you have to be stupid. You can't do this if you're brilliant because you wouldn't do it. You would say, "I'm not ready," but I was ready for anything because I just didn't fear it. I wasn't bright enough to do all that, and still, in the end, we got it done."

Growing up with Dad, I realized how much he enjoyed the challenge and excitement of working with the Sound-On-Sound format. He became one with Sound-On-Sound; it became instinct and intuition, and it didn't matter if he was playing the guitar or engineering.... he owned it.

Dad would say, "Maybe if it's to happen, it will happen."