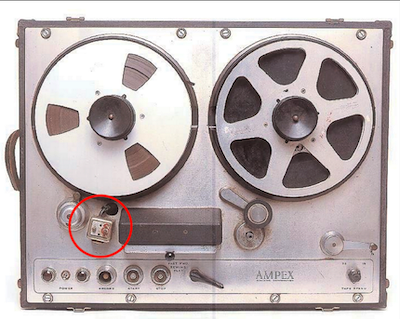

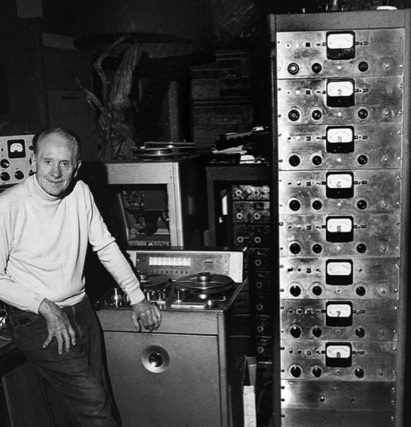

There's no doubt that the impetus for multi-tracking came from Les Paul. Lacking a means to play harmony parts and duets with himself, he modified a tape deck with an extra head and a switch to defeat the erase function and began recording sound-on-sound as early as 1949.

Using the earlier mono recorder and playing along with a track while recording over it entailed starting from scratch if a mistake was made on any subsequent take. There were no safety nets, and one couldn't "fix it in the mix," as became customary later. Although that involved greater risk and thus required intense concentration and technical expertise, it also made for more creative tension. Dad himself later admitted that he missed that.

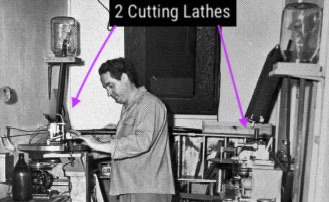

The 8-track concept came along while I was visiting Dad from Chicago in 1953. Dad took me to the studio where he and Mary were filming the "Listerine Show." Dad explains, " I was taking a rest and looking up at the sky. My manager asked what I was dreaming about. I said that recording using sound-on-sound was crazy. There's a better way: Stack the heads on top of the other — 1 through 8 — and align them so we could do self-sync with all the heads in-line. When I told my manager, 'I think it will change the world,' he told me I should do something about it."

The Ampex 8-track recorder employed Sel-Sync (selective synchronization), which streamlined the process of multiple recordings by allowing Dad to record the different parts in synchronization. But this method of recording, while it offered protection against losing prior tracks, lacked one key element that distinguished the earlier multiple recordings like "How High the Moon," namely the tension of having to get it right the first time, which made for a more spontaneous performance.

Gene's Personal Thoughts...

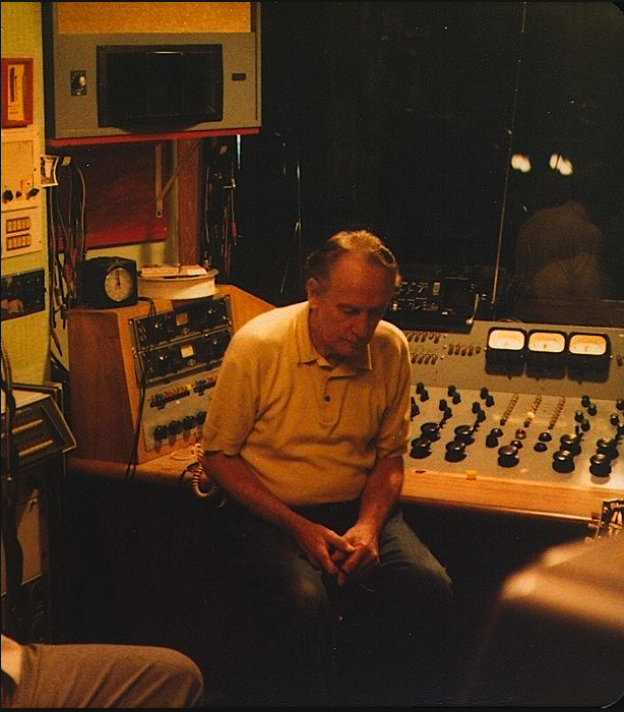

One day Dad was recording on the eight-track machine in the studio, and I had to leave to help out in the kitchen. When Dad came out for dinner, I asked how did it go. He was not sure which was not like him. After dinner, we went back to the studio to finish his overdub. He started and then stopped several times. I asked him what was wrong. He said, "it's not the same; I had more fun recording the old way." He explained that I could stop and pick it up later with the multi-track. With the old method, before I sat down, I had to know everything in my head; a one-take performance, that was it. He said, "I guess I'll get used to it in time."

I believe that Dad realized that using the 8-track recorder took away the adrenaline rush of making a record using his tried and true method of Sound-on-Sound. He grew up in the world of "Live One-Take," no turning back, and loved it. Oddly enough, Dad never made any of Les & Mary's hits using the multi-track machine. When an interviewer asked him, "Knowing both Sound-on-Sound and the 8-track recorder, what are your thoughts?" he answered, "I had more fun with Sound-on-Sound." I believe Dad was very pleased with the outcome of the 8-track recorder. It was the only invention he didn't need.

I think it became a gift . . . . from Les to the future generations.

“I never walk over to a recording machine until I know what I’m going to do. I don’t expect the machine to create a hit, because it only records what I have to say. This means I know what I’m going to do in the song’s intro, I know the tempo I’m going to play it in, I know what I have to say, and I know I have to say it in so many minutes and so many seconds. I know how the song is going to start out, and how it’s going to end. I know where it has to build up. I know the microphones I’m going to use, and I know the arrangement, and the instrumentation. And, with me, it’s from beginning to end. I invented multitracking, so I know that you can record parts separately and punch things in, but I don’t do that. My thinking is that a song has to have one feeling, and when you punch in, you’ve got one feeling over here, another feeling in the middle, and something different near the end. When you piece it together, that’s what comes out—pieces. The feeling doesn’t flow. Now, I’m not saying that you shouldn’t punch in if you missed a note. I’m just saying that, generally speaking, a song sounds better and more alive as a continuous performance of how you’re feeling.” —December 2005

AND THIS IS 14 YEARS BEFORE PRO TOOLS…

“Modern recording equipment is much more complicated than it needs to be. One of the first things I learned in the multitrack business is that the machine can run away from you. It can run you, instead of you running the machine.” —December 1977

"I was just curious; my brother would just throw the light switch and was never curious to find out what made the light light. Well, as soon as my mother left the house, I had a screwdriver and the plates off, and I'm gonna find out, if I get knocked on my ass, I'm gonna know that there's 110 volts there, whether it's alternating or direct current. I'm gonna know what's happening."

Les Paul The Inventor

Les Paul The Inventor

Les Paul and The Multi-Track Recorder

Karl F. Anderson, a retired Measurement Systems Engineer at NASA, states that Les Paul’s multitracking inventions and research were vital to space experts. Anderson explains that NASA was at a point in the 1950's where engineers were at a stalemate because they had a lot of data and they couldn’t manage all of this information in order to move the space program forward.

So when Paul came up with “Sound on Sound,” researchers at NASA thought if sound can be layered, they should be able to layer data in a similar way. Eventually, they were able to

adapt Paul’s multitracking techniques to accomplish

this to the U.S. Space Program.

"Dad's contributions went far beyond the music industry....."

John Glenn Climbs into Friendship 7